|

Crawdad

Family Astacidae

First posted August 1, 2004 Last

updated October 21, 2004

A crawdad at Caz in a defensive posture

Photo by David Nelson, specimen from

Austin Creek, July 23, 2004

The crawdad,

also know as the crawfish, mud

brother, and by many other names, is a constant

hit with the campers at Caz: they are easy to catch

and fun to play with. A common classroom biology subject,

it is also the only animal at camp that is commonly

eaten. And not just in the French Quarter in New Orleans:

it has a world-wide distribution and is eaten in many

countries. Crawfish feed on dead animals as well as

live pollywogs, small fish, and most anything that they

can catch. They are decapods, which means that they

have 10 legs.

The underside reveals the (from front

to rear) the mouthparts, 10 legs, swimmerets under the

tail

Photo by David Nelson, specimen from

Austin Creek, July 23, 2004

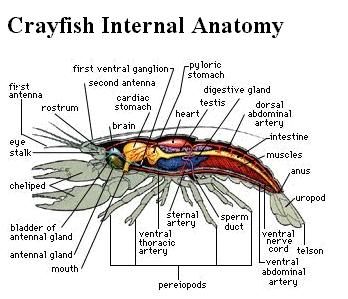

Crawfish Structure

The crayfish is typical of most shrimplike

crustaceans and is characterised by a joined head and

thorax, or midsection, and a segmented body, which in

the species at camp is a reddish brown, although the

larger ones have white markings around the base of the

main claw, or chelipeds.

The crayfish are usually seen are about 3 inches to

6 inches long, but if you look among the smaller rocks

you can find miniatures under 1 inch, or monsters greater

than 6 inches in the larger pools. There are about 150

species in North America, and there are more than 500

throughout the world. Among the smallest is the 1inch

long Cambarellus diminutus

of the south-eastern United States, and among the largest

is Astacopsis gouldi of Tasmania.

It can grow to reach 16 inches and its weight is about

8 pounds.

The crawfish is an excellent example of body segmentation,

a theme seen throughout the animal kingdom. The head

has three pairs of sensory antennae (two pair are very

small and usually overlooked; see the photographs below)

and a pair of eyes on movable stalks. The "legs",

or more properly, appendages,

or pereiopods, all attach

to the thorax. As noted above, there are 10 legs. Note

that the animal is bilaterally symmetric,

which means its right side and its left side are the

same. This is another theme seen throughout almost all

of the animal kingdom. The 10 legs, therefore, are organized

as five pairs of legs. The first pair are the large

claws, called chelipeds. Watch

a crawdad at the bottom of a pool at Caz and you can

see that the crawdad extends in front of its body while

moving. These strong pinchers are specialised for cutting,

capturing food, attack, and defence. A pinch can hurt!

The next two pair of legs each have miniature claws

and are used for feeding as well as walking. Watch a

crawdad in a pool and you will see it pick up food with

the large claws and then pass it to these smaller claws,

then to its mouthparts. When you pick one up, be careful

these don't nip you! They are not powerful enough to

hurt, just tickle. The rear two pair of legs end in

points, not claws, and are used only for walking. The

large muscular abdomen is attached to the tail, which

is used in short bursts to escape enemies, which include

raccoons (and campers!). The crayfish also has five

pairs of swimmerets which

are under the abdomen. All of these "legs"

can be regenerated if broken off.

Crayfish have a shell, or carapace,

which is its outside skeleton, or exoskeleton.

This jointed shell provides protection and allows movement,

but limits growth. As a result, the crayfish regularly

gets too big for its skeleton, sheds it, and grows a

new larger one. (See below for a great science activity

that you can do with the shed shell.) This is called

molting, and occurs six to ten times during the first

year of rapid growth, but less often during the second

year. For a few days following each molt, crayfish have

soft exoskeletons and are more vulnerable to predators.

|

|

|

You have a skeleton on the

inside, called an endoskeleton.

These bones help you to move and protect your

brain, heart, lungs, and other soft parts. |

|

The crawfish has its skeleton

on the outside, called a shell or an exoskeleton.

This shell does the same things as your skeleton:

helps it move and protects is brain, heart,

and other soft parts. |

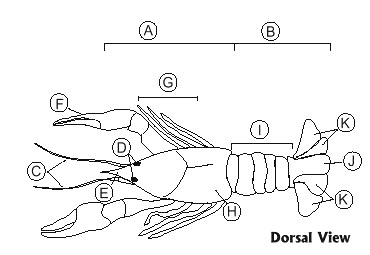

This is a diagram of a crawdad, from

the top, or dorsal, side. A is the

cephalothorax and B is the tail.

C marks the second antennae; not

shown are the two pair of first antennae. D

indicates the eyes, E is the rostrum,

a projection out over the eyes. F

refers to the main claws, called the chelipeds, specialized

for fighting, defending, and holding onto food. G

shows the peripods, or walking legs. They also are

used in feeding and probing crevices for food. The

front two pairs have claws, the back two pairs are

pointed and clawless. H is the carapace,

or shell over the cephalothorax, that protects the

internal organs. J is the uropod,

or center part of the tail, and K

marks the telsons, or lateral parts of the tail. Swimmerets,

not shown, are on the underside of the tail, I.

|

|

Here you can

see the two pair of first antennae

that are not shown in the diagram above.

They originate from just above

and between the secondary antennae.

Photo by David Nelson, specimen from Austin

Creek, July 23, 2004 |

It is fun to try to catch a crawfish,

place them in a shallow container and watch them crawl

around. Try to draw one and you will find youself

"seeing" more than you did before!

Crayfish Behaviour

Crayfish often conceal themselves under

rocks or logs. They are most active at night, when

they feed largely on snails, algae, moss and other

vegetation, insect larvae, worms, fish, tadpoles,

almost any kind of dead animal matter, old shed carapaces

(crawdad shells), and even other crawfish. Studies

show that adults (one year old) become most active

at dusk and continue heavy feeding activity until

daybreak. Young crayfish are more likely to be the

ones out during bright sunny days, while the older

crayfish are more active on cloudy days and during

the night. Although they mainly feed in the water,

they do venture out a little onto land, but they are

vulnerable to predation and breathe by gills, so terrestrial

activity is limited. Terrestrial activity allows them

to escape from isolated pools when the creek dries

up. General movement is always a slow walk. If you

sit quietly on a rock, you can see them walk about

the bottom, feeding and fighting, holding their large

claws out in front. Small crawfish will always back

away from a larger one. If startled, crayfish use

rapid flips of their tail to swim backwards and escape

danger.

Most crayfish live short lives, usually

less than two years. Therefore, rapid, high-volume

reproduction is important for the continuation of

the species. Many crayfish become sexually mature

and mate in the October or November after they're

born, but fertilisation and egg laying usually occur

the following spring. The fertilised eggs are attached

to the female' swimmerets on the underside of her

jointed abdomen. There the 10 to 800 eggs change from

dark to translucent as they develop. The egg-carrying

female is said to be ‘in berry,’ because

the egg mass looks something like a berry. Females

are often seen "in berry" during May or

June. The eggs hatch in 2 to 20 weeks, depending on

water temperature. The newly-hatched crayfish stay

attached to their mother until shortly after their

second molt. If you want to find baby crawfish, look

in the small stones and gravel along the edges of

the pools of Austin Creek.

Crayfish as

Food

Most people know that crayfish are good

to eat. In some places in the US, such as Louisiana,

crayfish are a specialty and are served up boiled

in spices, baked, fried, or served with noodles, rice,

etc. Crawfish etouffee is a famous dish in New Orleans!

It is delicious! Here is a recipe from Nurse

Di who grew up in Louisiana:

2 tablespoons flour

2 tablespoons vegetable oil

3 cans chicken broth

1 medium bell pepper, chopped

2 medium onions, choped

3 celery ribs, chopped

1 can cream of mushroom soup

1 (15 ounces) can tomato sauce

1 tablespoon parsley flakes

1 teaspoon Accent seasoning

3 cloves garlic, minced

1 teaspoon salt

1/2 teaspoon pepper

1/4 teaspoon basil

1/4 teaspoon poultry seasoning

1 teaspoon Worcestershire sauce

1 teaspoon lemon juice

2 lbs crawfish tails

1/2 cup chopped green onions

hot cooked rice

| SCIENTIFIC

CLASSIFICATION

Crawdad

CLASS: Arthopoda

ORDER: Crustacea

SUBORDER: Decapoda

FAMILY: Astacodae

SUBFAMILY:

GENUS & SPECIES: |

Scientific Classification

Crayfish are part of the order Decapoda

constituting the families Astacidae (Northern Hemisphere),

Parastacidae, or Austroastracidae (Southern Hemisphere).

The most common genera of North America include Procambarus,

Orconectes, Faxonella, Cambarus, Cambarellus, and

Pacifastacus. Austropotamobius is the most common

genus of Europe. The genus Astacus occurs in Europe,

the genus Cambaroides in East Asia. The arthopod class

also includes centipedes, crustaceans, insects, millipedes,

mites, scorpions and spiders.

Fun Science

Activity

Crawdads shed their skin, called the

exoskeleton, as they grow. This gives

rise to a great activity: mounting the shed shell.

These can be gathered from the streambottom. Place

them in a plastic bag to keep them moist. Clean the

shell off in fresh water then lay it out on a piece

of cardboard. If you position the antennae, claws,

tail, and legs in a realistic position, it will harden

in a day or two (see photo). You can reposition any

part later by moistening the joints then re-drying.

Shell being positioned for drying

Photograph by David Nelson, July 26,

2004

A finished exoskeleton

References

The Brigham

Young University website is full of scientific

information.

Acknowledgements

The crawdad diagram is from the Louisian

Marine Education Resources website.

The description of the structure, behaviour, internal

anatomy, and science is taken or adapted from the Crayfish

Corner.

|

|