Wrist Fracture

This is material I originally wrote in 2005 for the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgery, for their patient education website. The original version is posted on their website but I have updated it here; the original is now at least four years out of date. I tried to write it in plain English, but included the medical terms in quotes so that you can understand a doctor if they use the terms. I am posting this updated version here so that you can have further information about your fracture. See also my other page on distal radius fractures.

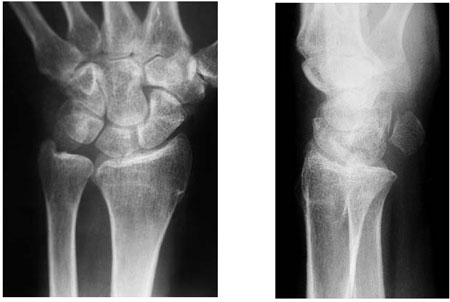

The larger bone shown above is called the radius. It is on the thumb side of the arm.

The lower bone is called the ulna and is on the little finger side of the arm.

What is it?

When someone falls on their outstretched hand, they sometimes get a "broken wrist." The bone that is usually broken is called the radius. It is the larger bone on the upper side of the photograph above. The end toward the wrist is called the distal end. The medical term for “broken bone” is fracture. Therefore, the medical term for the most common type of "broken wrist" is a distal radius fracture (that is, the larger forearm bone is broken near the wrist).

This kind of fracture is very common. In fact, the radius is the most commonly broken bone in the arm. It usually happens when you fall and land on your outstretched hands. It can also happen in a car accident, bike accident, skiing accident, and similar situations. Sometimes, the other forearm bone (the ulna) is also broken, which would be called a distal ulna fracture.

The fracture was first described by an Irish surgeon and anatomist, Abraham Colles, in 1814 in the Edinburgh Medical Surgical Journal, so it is sometimes called a "Colles' fracture."

A broken wrist usually causes pain and swelling, and frequently causes a deformity, making the wrist look bent. See your doctor for a diagnosis. The doctor will take an xray of the wrist. The fracture (broken bone) is almost always about one inch from the end of the bone. If the fracture extends into the joint, it is called an intra-articular fracture; if it does not, it is called an extra-articular fracture ("articular” means “joint”). If the fracture breaks the skin, it is called an open fracture (the old term for this was a compound fracture, but this term is not used anymore). If the bone is broken into many pieces, not just two, it is called a comminuted fracture. A fracture is more difficult to treat if it is intra-articular, open, or comminuted.

This is an xray of a normal wrist, looking at it from the front (left) and from the side (right). In the left picture, the radius is the larger bone in the photograph.

This is an xray of a typical distal radius fracture, looking at it from the front (left) and from the side (right). In the pictures, the fracture (broken bone) is indicated by the arrows. The other black spaces are the joints.

Risk Factors/Prevention

Many disttal radius fractures in patients over 60 are be due to osteoporosis (decreased density of the bones) if the fall was relatively minor (a fall from a standing position). They can happen even in healthy bones if the trauma was severe enough (for example, a car accident or a fall off a bike). The best prevention is to maintain good bone health and avoid osteoporosis and falls. Older patients who have problems keeping their balance need special attention to prevent falls. Wrist guards worn on the forearms may help to prevent some fractures, but they will not prevent them all.

Symptoms

When you have a distal radius fracture, you will almost always have a history of a fall or some other kind of trauma. You will usually have pain and swelling in the forearm or wrist. You may have a deformity in the shape of the wrist if the fracture is bad enough. The presence of bruising (black and blue discoloration) is common. See your doctor if you have enough pain in your arm to stop you from using it normally. You may want to go directly to an orthopaedist (bone doctor), who can usually take an X-ray right in the office and tell you what is going on. If your doctor's office is closed, the injury is not very painful and the wrist is not deformed, you can usually wait until the next day. Go to the emergency room if the injury is very painful, the wrist is deformed, you have numbness, or your fingers are not pink. You may want to protect the wrist with a splint and apply ice to the wrist and elevate it until you get to the doctor's office.

Treatment Options

There are many treatment choices. Your orthopaedic surgeon will describe what options are right for you. The choice depends on many factors, such as the nature of your fracture, your age and activity level, and your surgeon's personal preferences. The following is a general discussion of the possible options, just so you have a better idea of what your orthopaedic surgeon might recommend for you.

One choice is to leave the bone the way it is, if the bone is in a pretty good position. Your doctor may apply a plaster cast until the bone heals. Generally, if the bone was not pushed back into position, your doctor will generally get xrays in about three weeks, to be sure it has not moved. The cast generally stays on for about six weeks.

A second option is to push the bones back into place. This is done if the position (alignment) of your bone is not good and likely to limit the future use of your arm. The medical term for correcting the deformed bone by means of pushing on the bone but not making an incision is closed reduction. After the bone is properly aligned, a splint or cast may be placed on your arm. A splint is usually used for the first few days, to allow for a small amount of normal swelling. The splint is usually changed to a cast in a few days to a week or so later, after the swelling goes down, and changed two or three weeks later as the swelling goes down more and the cast gets loose. X-rays are taken, depending on the nature of the facture, usually at weekly intervals for three weeks, when the cast is usually changed, and then at six weeks, when the cast is removed. At that point, physical therapy is often started to help improve motion and function of the injured wrist.

Treatment Options: Surgical

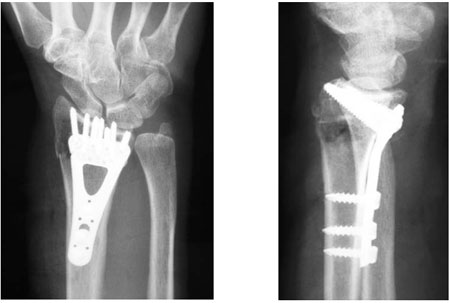

If your orthopaedic surgeon feels that the position of the bone is not acceptable for the future function of your arm, and that it cannot be corrected just by pushing on it or if your surgeon does not think that it can be kept corrected in a cast, he or she may recommend an operation. There are many ways of performing surgery, including reducing the fracture in the operating room without making an incision (operative closed reduction), or by making an incision (open reduction) to improve the alignment of the bone. In the operating room, your orthopaedic surgeon may choose to hold the bone in the correct position with only a cast, or by inserting metal (usually stainless steel or titanium) pins, a plate and screws, an external fixator, or any combination of these techniques. Some examples follow.

This is an example of a plate and screws inserted at surgery to hold the bones in the proper place, after the surgeon performed an open reduction. Most of the time, the plate stays in permanently and causes no problem. (No, you will usually not set off the airport alarm!)

This is an example of an external fixator placed into the bones to hold them in the correct place. Sometimes a surgeon uses this option when the bone is broken into too many small pieces ("comminuted") to be able to place a plate and screws. The external fixator is removed in the office in about six to eight weeks after surgery. Surprisingly, it does not hurt and anesthesia is usually not needed or even desired.

What Can I Expect While my Bone Is Healing?

This is a very simple question. Unfortunately it does not have a simple answer. The kinds of distal radius fractures are so varied and the treatment options are so broad that it is hard to describe what to expect. Most fractures hurt moderately for a few days to a couple of weeks. Many patients find that using ice, elevation (holding their arm up above their heart), and simple, non-prescription medications for pain relief are all that are needed. One combination is ibuprofen (sold as a generic or under the brand names Motrin® or Advil®) plus acetaminophen (sold under the brand name Tylenol®, and also as a generic, often marked on the box "non-aspirin pain reliever"). The combination of both ibuprofen plus acetaminophen is much more effective than either one alone (the medical term for this is synergistic). If pain is severe, patients may need to take a prescription strength medication, often a narcotic, for a few days. Discuss these options with your doctor.

Casts and splints must be kept dry, so use a plastic bag over your arm while you are showering. If you do get it wet, it will not dry very easily (you can try to use a hair dryer on the cool setting). There are no real "waterproof" casts, but there are some options available that have their pluses and minuses. Discuss this with your doctor.

Most surgical incisions must be kept clean and dry for five days or until the sutures (stitches) are removed, whichever occurs later.

What Can I Expect After my Bone Has Healed?

Everyone wants to know, "Can I return to all my former activities, and when?" This is a great question that also seems rather simple and straightforward, but the answer is complex. Most patients do return to all their former activities, but what will happen in your case depends on the nature of your injury, the kind of treatment you and your surgeon decide upon, and how your body responds to the treatment. You will need to discuss your case with your doctor for the specifics of your case, but some generalizations can be made.

- Most patients have their cast taken off at about six weeks.

- Most patients will start physical therapy, if their doctor feels it is needed, within a few days to weeks after surgery, or right after the last cast is taken off.

- Most patients will be able to resume light activities such as swimming or working out the lower body in the gym within a month or two after the cast is taken off, or after surgery.

- Most patients can resume vigorous physical activities, such as skiing or football, between three and six months after the injury.

- Almost all patients will have some stiffness in the wrist, which will generally diminish in the month or two after the cast is taken off or after surgery, and will continue to improve for at least two years.

- You should expect your recovery to take at least a year. You will still feel some pain with vigorous activities for about that long. Some residual stiffness or ache is to be expected for two years or possibly permanently, especially for high energy injuries (such as motorcycle crashes, etc.), in patients over 50, or in patients who have some osteoarthritis. However, the good news is that the stiffness is usually minor and may not affect the overall function of the arm.

Remember, these are general guidelines and may not apply to you and your fracture. Ask your doctor for specifics in your case. Your doctor knows that returning to activities is important to you.

Finally, osteoporosis is a factor in many adult wrist fractures, as many as 250,000 per year in the US. It has been suggested that people who suffer a wrist fracture may need to be screened for osteoporosis, especially if they have other risk factors. Ask your doctor if you need to be screened or treated for osteoporosis.